Continuous delivery is an approach where teams release quality products frequently and predictably from source code repository to production in an automated fashion.

What is Continuous Delivery

Continuous Delivery is the ability to get changes of all types - including new features, configuration changes, bug fixes and experiments - into production, or into the hands of users, safely and quickly in a sustainable way.

The goal of continuous delivery is to make deployments - whether of a large-scale distributed system, a complex production environment, an embedded system, or an app - predictable, routine affairs that can be performed on demand.

We achieve all this by ensuring our code is always in a deployable state, even in the face of teams of thousands of developers making changes on a daily basis. We thus completely eliminate the integration, testing and hardening phases that traditionally followed "dev complete", as well as code freezes.

Why Continuous Delivery

It is often assumed that if we want to deploy software more frequently, we must accept lower levels of stability and reliability in our systems. In fact, peer-reviewed research shows that this is not the case. High performance teams consistently deliver services faster and more reliably than their low performing competition. This is true even in highly regulated domains such as financial services and government. This capability provides an incredible competitive advantage for organizations that are willing to invest the effort to pursue it.

- Firms with high-performing IT organizations were twice as likely to exceed their profitability, market share and productivity goals.

- High performers achieved higher levels of both throughput and stability.

- The use of continuous delivery practices including version control, continuous integration, and test automation predicts higher IT performance.

- Culture is measurable and predicts job satisfaction and organizational performance.

- Continuous Delivery measurably reduces both deployment pain and team burnout.

The practices at the heart of continuous delivery help us achieve several important benefits:

-

Low risk releases. The primary goal of continuous delivery is to make software deployments painless, low-risk events that can be performed at any time, on demand. By applying patterns such as blue-green deployments it is relatively straightforward to achieve zero-downtime deployments that are undetectable to users.

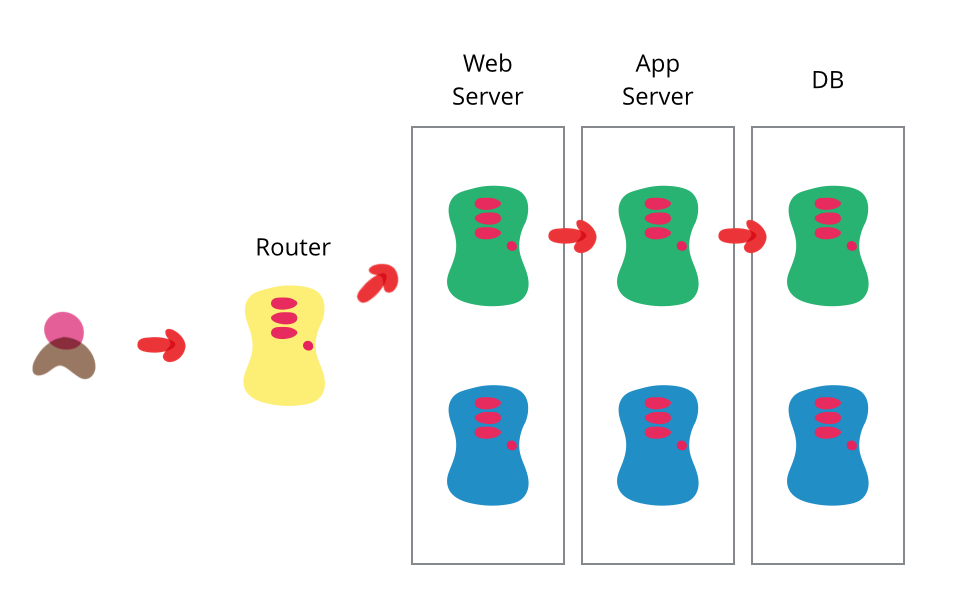

:::info blue-green deployment

One of the challenges with automating deployment is the cut-over itself, taking software from the final stage of testing to live production. We usually need to do this quickly in order to minimize downtime. The blue-green deployment approach does this by ensuring we have two production environments, as identical as possible. At any time one of them, let's say blue for the example, is live. As we prepare a new release of our software we do our final stage of testing in the green environment. Once the software is working in the green environment, we switch the router so that all incoming requests go to the green environment - the blue one is now idle.

Blue-green deployment also gives us a rapid way to rollback - if anything goes wrong we switch the router back to our blue environment. There's still the issue of dealing with missed transactions while the green environment was live, but depending on our design we may be able to feed transactions to both environments in such a way as to keep the blue environment as a backup when the green is live. Or we may be able to put the application in read-only mode before cut-over, run it for a while in read-only mode, and then switch it to read-write mode. That may be enough to flush out many outstanding issues.

The two environments need to be different but as identical as possible. In some situations they can be different pieces of hardware, or they can be different virtual machines running on the same (or different) hardware. They can also be a single operating environment partitioned into separate zones with separate IP addresses for the two slices.

Once we've put our green environment live and we're happy with its stability, we then use the blue environment as our staging environment for the final testing step for our next deployment. When we are ready for our next release, we switch from green to blue in the same way that we did from blue to green earlier. That way both green and blue environments are regularly cycling between live, previous version (for rollback) and staging the next version.

An advantage of this approach is that it's the same basic mechanism as we need to get a hot-standby working. Hence this allows us to test our disaster-recovery procedure on every release.

The fundamental idea is to have two easily switchable environments to switch between, there are plenty of ways to vary the details. One project did the switch by bouncing the web server rather than working on the router. Another variation would be to use the same database, making the blue-green switches for web and domain layers.

Databases can often be a challenge with this technique, particularly when we need to change the schema to support a new version of the software. The trick is to separate the deployment of schema changes from application upgrades. So first apply a database refactoring to change the schema to support both the new and old version of the application, deploy that, check everything is working fine so we have a rollback point, then deploy the new version of the application. (And when the upgrade has bedded down remove the database support for the old version.) :::

-

Faster time to market. It's common for the integration and test/fix phase of the traditional phased software delivery lifecycle to consume weeks to even months. When teams work together to automate the build and deployment, environment provisioning, and regression testing process, developers can incorporate integration and regression testing into their daily work and completely remove these phases. We also avoid the large amount of re-work that plague the phased approach.

-

Higher quality and Better products. When developers have automated tools that discover regressions within minutes, teams are freed to focus their effort on user research and higher level testing activities such as exploratory testing, usability testing, and performance and security testing. By building a deployment pipeline, these activities can be performed continuously throughout the delivery process, ensuring quality is built into products and services from the beginning. Continuous delivery makes it economic to work in small batches. This means we can get feedback from users throughout the delivery lifecycle based on working software.

-

Lower costs. Any successful software product or service will evolve significantly over the course of its lifetime. By investing in build, test, deployment and environment automation, we substantially reduce the cost of making and delivering incremental changes to software by eliminating many of the fixed costs associated with the release process.

-

Happier teams. Continuous Delivery makes releases less painful and reduces team burnout. Furthermore, when we release more frequently, software delivery teams can engage more actively with users, learn which ideas work and which don't, and see first-hand then outcomes of the work they have done. By removing low-value painful activities accociated with software delivery, we can fodus on what we care about most - continuous delighting our users.

Continuous delivery is about continuous, daily improvement - the constant discipline of pursuing higher performance by following the heuristic "if it hurts, do it more often, and bring the pain forward."

Principles

There are five principles at the heart of continuous delivery:

- Build quality in

- Work in small batches

- Computers perform repetitive tasks, people solve problems

- Relentlessly pursue continuous improvement

- Everyone is responsible

It's easy to get bogged down in the details of implementing continuous delivery - tools, architecture, practices, politics - if you find yourself lost, try revisiting these principles and you may find it helps you refocus on what's important.

Build Quality In

W. Edwards Deming, a key figure in the history of the Lean movement, offered 14 key principles for management. Principle three states, "Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality. Eliminate the need for inspection on a mass basis by building quality into the product in the first place".

It's much cheaper to fix problems and defects if we find them immediately - ideally before they are ever checked into version control, by running automated tests locally. Finding defects downstream through inspection (such as manual testing) is time-consuming, requiring significant triage. Then we must fix the defect, trying to recall what we were thinking when we introduced the problem days or perhaps even weeks ago.

Creating and evolving feedback loops to detect problems as early as possible is essential and never-ending work in continuous delivery. If we find a problem in our exploratory testing, we must not only fix it, but then ask: How could we have caught the problem with an automated acceptance test? When an acceptance test fails, we should ask: Could we have written a unit test to catch this problem?

Work in Small Batches

In traditional phased approaches to software development, handoffs from dev to test or test to IT operations consist of whole releases: months worth of work by teams consisting of tens or hundreds of people.

In continuous delivery, we take the opposite approach, and try and get every change in version control as far towards release as we can, getting comprehensive feedback as rapidly as possible.

Working in small batches has many benefits. It reduces the time it takes to get feedback on our work, makes it easier to triage and remediate problems, increases efficiency and motivation, and prevents us from succumbing to the sunk cost fallacy.

The reason we work in large batches is because of the large fixed cost of handing off changes. A key goal of continuous delivery is to change the economics of the software delivery process to make it economically viable to work in small batches so we can obtain the many benefits of this approach.

A key goal of continuous delivery is to change the economics of the software delivery process to make it economically viable to work in small batches so we can obtain the many benefits of this approach

Relentlessly Pursue Continuous Improvement

Continuous improvement, or kaizen in Japanese, is another key idea from the Lean movement. Taiichi Ohno, a key figure in the history of the Toyota company, once said,

"Kaizen opportunitites are infinite. Don't think you have made things better than before and be at ease… This would be like the student who becomes proud because they bested their master two times out of three in fencing. Once you pick up the sprouts of kaizen ideas, it is important to have the attitude in our daily work that just underneath one kaizen idea is yet another one".

Don't treat transformation as a project to be embarked on and then completed so we can return to business as usual. The best organizations are those where everybody treats improvement work as an essential part of their daily work, and where nobody is satisfied with the status quo.

Everyone is Responsible

In high performing organizations, nothing is "somebody else's problem." Developers are responsible for the quality and stability of the software they build. Operations teams are responsible for helping developers build quality in. Everyone works together to achieve the organizational level goals, rather than optimizing for what’s best for their team or department.

When people make local optimizations that reduce the overall performance of the organization, it's often due to systemic problems such as poor management systems such as annual budgeting cycles, or incentives that reward the wrong behaviors. A classic example is rewarding developers for increasing their velocity or writing more code, and rewarding testers based on the number of bugs they find.

Most people want to do the right thing, but they will adapt their behaviour based on how they are rewarded. Therefore, it is very important to create fast feedback loops from the things that really matter: how customers react to what we build for them, and the impact on our organization.

Foundations - Prerequisites for Continuous Delivery

Configuration Management

Automation plays a vital role in ensuring we can release software repeatably and reliably. One key goal is to take repetitive manual processes like build, deployment, regression testing and infrastructure provisioning, and automate them. In order to achieve this, we need to version control everything required to perform these processes, including source code, test and deployment scripts, infrastructure and application configuration information, and the many libraries and packages we depend upon. We also want to make it straightforward to query the current -and historical - state of our environments.

We have two overriding goals:

- Reproducibility: We should be able to provision any environment in a fully automated fashion, and know that any new environment reproduced from the same configuration is identical.

- Traceability: We should be able to pick any environment and be able to determine quickly and precisely the versions of every dependency used to create that environment. We also want to be able to compare previous versions of an environment and see what has changed between them.

These capabilities give us several very important benefits:

- Disaster recovery: When something goes wrong with one of our environments, for example a hardware failure or a security breach, we need to be able to reproduce that environment in a deterministic amount of time in order to be able to restore service.

- Auditability: In order to demonstrate the integrity of the delivery process, we need to be able to show the path backwards from every deployment to the elements it came from, including their version. Comprehensive configuration management, combined with deployment pipelines, enable this.

- Higher quality: The software delivery process is often subject to long delays waiting for development, testing and production environments to be prepared. When this can be done automatically from version control, we can get feedback on the impact of our changes much more rapidly, enabling us to build quality in to our software.

- Capacity management: When we want to add more capacity to our environments, the ability to create new reproductions of existing servers is essential. This capability, using OpenStack for example, enables the horizontal scaling of modern cloud-based distributed systems.

- Response to defects: When we discover a critical defect, or a vulnerability in some component of our system, we want to get a new version of our software released as quickly as possible. Many organizations have an emergency process for this type of change which goes faster by bypassing some of the testing and auditing. This presents an especially serious dilemma in safety-critical systems. Our goal should be to be able to use our normal release process for emergency fixes - which is precisely what continuous delivery enables, on the basis of comprehensive configuration management.

As environments become more complex and heterogeneous, it becomes progressively harder to achieve these goals. Achieving perfect reproducibility and traceability to the last byte for a complex enterprise system is impossible (apart from anything else, every real system has state). Thus a key part of configuration management is working to simplify our architecture, environments and processes to reduce the investment required to achieve the desired benefits.

Configuration Management Learning Resources

Continuous Integration

Combining the work of multiple developers is hard. Software systems are complex, and an apparently simple, self-contained change to a single file can easily have unintended consequences which compromise the correctness of the system. As a result, some teams have developers work isolated from each other on their own branches, both to keep trunk/master stable, and to prevent them treading on each other’s toes.

However, over time these branches diverge from each other. While merging a single one of these branches into mainline is not usually troublesome, the work required to integrate multiple long-lived branches into mainline is usually painful, requiring significant amounts of re-work as conflicting assumptions of developers are revealed and must be resolved.

Teams using long-lived branches often require code freezes, or even integration and stabilization phases, as they work to integrate these branches prior to a release. Despite modern tooling, this process is still expensive and unpredictable. On teams larger than a few developers, the integration of multiple branches requires multiple rounds of regression testing and bug fixing to validate that the system will work as expected following these merges. This problem becomes exponentially more severe as team sizes grow, and as branches become more long-lived.

The practice of continuous integration was invented to address these problems. CI (continuous integration) follows the XP (extreme programming) principle that if something is painful, we should do it more often, and bring the pain forward. Thus in CI developers integrate all their work into trunk (also known as mainline or master) on a regular basis (at least daily). A set of automated tests is run both before and after the merge to validate that no regressions are introduced. If these automated tests fail, the team stops what they are doing and someone fixes the problem immediately.

Thus we ensure that the software is always in a working state, and that developer branches do not diverge significantly from trunk. The benefits of continuous integration are very significant - higher levels of throughput, more stable systems, and higher quality software. However the practice is still controversial, for two main reasons.

First, it requires developers to break up large features and other changes into smaller, more incremental steps that can be integrated into trunk/master. This is a paradigm shift for developers who are not used to working in this way. It also takes longer to get large features completed. However in general we don't want to optimize for the speed at which developers can declare their work "dev complete" on a branch. Rather, we want to be able to get changes reviewed, integrated, tested and deployed as fast as possible - and this process is an order of magnitude faster and cheaper when the changes are small and self-contained, and the branches they live on are short-lived. Working in small batches also ensures developers get regular feedback on the impact of their work on the system as a whole - from other developers, testers, customers, and automated performance and security tests—which in turn makes any problems easier to detect, triage, and fix.

Second, continuous integration requires a fast-running set of comprehensive automated unit tests. These tests should be comprehensive enough to give a good level of confidence that the software will work as expected, while also running in a few minutes or less. If the automated unit tests take longer to run, developers will not want to run them frequently, and they will become harder to maintain. Creating maintainable suites of automated unit tests is complex and is best done through test-driven development (TDD), in which developers write failing automated tests before they implement the code that makes the tests pass. TDD has several benefits, the most important of which is that it ensures developers write code that is modular and easy to test, reducing the maintenance cost of the resulting automated test suites. But TDD is still not sufficiently widely practiced.

Despite these barriers, helping software development teams implement continuous integration should be the number one priority for any organization wanting to start the journey to continuous delivery. By creating rapid feedback loops and ensuring developers work in small batches, CI enables teams to build quality into their software, thus reducing the cost of ongoing software development, and increasing both the productivity of teams and the quality of the work they produce.

Continuous Integration Learning Resources

Continuous Testing

The key to building quality into our software is making sure we can get fast feedback on the impact of changes. Traditionally, extensive use was made of manual inspection of code changes and manual testing (testers following documentation describing the steps required to test the various functions of the system) in order to demonstrate the correctness of the system. This type of testing was normally done in a phase following “dev complete”. However this strategy have several drawbacks:

- Manual regression testing takes a long time and is relatively expensive to perform, creating a bottleneck that prevents us releasing software more frequently, and getting feedback to developers weeks (and sometimes months) after they wrote the code being tested.

- Manual tests and inspections are not very reliable, since people are notoriously poor at performing repetitive tasks such as regression testing manually, and it is extremely hard to predict the impact of a set of changes on a complex software system through inspection.

- When systems are evolving over time, as is the case in modern software products and services, we have to spend considerable effort updating test documentation to keep it up-to-date.

In order to build quality in to software, we need to adopt a different approach.

The more features and improvements go into our code, the more we'll need to test to make sure that all our system works properly. And then for each bug we fix, it would be wise to check that they don't get back in newer releases. Automation is key to make this possible and writing tests sooner rather than later will become part of our development workflow.

Once we have continuous integration and test automation in place, we create a deployment pipeline. In the deployment pipeline pattern, every change runs a build that

- creates packages that can be deployed to any environment and

- runs unit tests (and possibly other tasks such as static analysis), giving feedback to developers in the space of a few minutes.

Packages that pass this set of tests have more comprehensive automated acceptance tests run against them. Once we have packages that pass all the automated tests, they are available for deplyment to other environments.

In the deployment pipeline, every change is effectively a release candidate. The job of the deployment pipeline is to catch known issues. If we can't detect any known problems, we should feel totally comfortable releasing any packages that have gone through it. If we aren't, or if we discover defects later, it means we need to improve our pipeline, perhaps adding or updating some tests.

Our goal should be to find problems as soon as possible, and make the lead time from check-in to release as short as possible. Thus we want to parallelize the activities in the deployment pipeline, not have many stages executing in series. If we discover a defect in the acceptance tests, we should be looking to improve our unit tests (most of our defects should be discovered through unit testing).

Different Types of Software Testing

Unit Tests

Unit tests are very low level and close to the source of an application. They consist in testing individual methods and functions of the classes, components, or modules used by our software. Unit tests are generally quite cheap to automate and can run very quickly by a continuous integration server.

Integration Tests

Integration tests verify that different modules or services used by our application work well together. For example, it can be testing the interaction with the database or making sure that microservices work together as expected. These types of tests are more expensive to run as they require multiple parts of the application to be up and running.

Functional Tests

Functional tests focus on the business requirements of an application. They only verify the output of an action and do not check the intermediate states of the system when performing that action.

There is sometimes a confusion between integration tests and functional tests as they both require multiple components to interact with each other. The difference is that an integration test may simply verify that we can query the database while a functional test would expect to get a specific value from the database as defined by the product requirements.

End-to-End Tests

End-to-end testing replicates a user behavior with the software in a complete application environment. It verifies that various user flows work as expected and can be as simple as loading a web page or logging in or much more complex scenarios verifying email notifications, online payments, etc...

End-to-end tests are very useful, but they're expensive to perform and can be hard to maintain when they're automated. It is recommended to have a few key end-to-end tests and rely more on lower level types of testing (unit and integration tests) to be able to quickly identify breaking changes.

Acceptance Tests

Acceptance tests are formal tests that verify if a system satisfies business requirements. They require the entire application to be running while testing and focus on replicating user behaviors. But they can also go further and measure the performance of the system and reject changes if certain goals are not met.

Performance Tests

Performance tests evaluate how a system performs under a particular workload. These tests help to measure the reliability, speed, scalability, and responsiveness of an application. For instance, a performance test can observe response times when executing a high number of requests, or determine how a system behaves with a significant amount of data. It can determine if an application meets performance requirements, locate bottlenecks, measure stability during peak traffic, and more.

Smoke Tests

Smoke tests are basic tests that check the basic functionality of an application. They are meant to be quick to execute, and their goal is to give us the assurance that the major features of our system are working as expected.

Smoke tests can be useful right after a new build is made to decide whether or not we can run more expensive tests, or right after a deployment to make sure that they application is running properly in the newly deployed environment.

Implementing Continuous Delivery

Organizations attempting to deploy continuous delivery tend to make two common mistakes. The first is to treat continuous delivery as an end-state, a goal in itself. The second is to spend a lot of time and energy worrying about what products to use.

Evolutionary Architecture

In the context of enterprise architecture there are typically multiple attributes we are concerned about, for example availability, security, performance, usability and so forth. In continuous delivery, we introduce two new architectural attributes:

- testability

- deployability

In a testable architecture, we design our software such that most defects can (in principle, at least) be discovered by developers by running automated tests on their workstations. We shouldn’t need to depend on complex, integrated environments in order to do the majority of our acceptance and regression testing.

In a deployable architecture, deployments of a particular product or service can be performed independently and in a fully automated fashion, without the need for significant levels of orchestration. Deployable systems can typically be upgraded or reconfigured with zero or minimal downtime.

Where testability and deployability are not prioritized, we find that much testing requires the use of complex, integrated environments, and deployments are "big bang" events that require that many services are released at the same time due to complex interdependencies. These "big bang" deployments require many teams to work together in a carefully orchestrated fashion with many hand-offs, and dependencies between hundreds or thousands of tasks. Such deployments typically take many hours or even days, and require scheduling significant downtime.

Designing for testability and deployability starts with ensuring our products and services are composed of loosely-coupled, well-encapsulated components or modules

We can define a well-designed modular architecture as one in which it is possible to test or deploy a single component or service on its own, with any dependencies replaced by a suitable test double, which could be in the form of a virtual machine, a stub, or a mock. Each component or service should be deployable in a fully automated fashion on developer workstations, test environments, or in production. In a well-designed architecture, it is possible to get a high level of confidence the component is operating properly when deployed in this fashion.

Test Double is a generic term for any case where you replace a production object for testing purposes. There are various kinds of double:

- Dummy objects are passed around but never actually used. Usually they are just used to fill parameter lists.

- Fake objects actually have working implementations, but usually take some shortcut which makes them not suitable for production (an InMemoryTestDatabase is a good example).

- Stubs provide canned answers to calls made during the test, usually not responding at all to anything outside what's programmed in for the test.

- Spies are stubs that also record some information based on how they were called. One form of this might be an email service that records how many messages it was sent.

- Mocks are pre-programmed with expectations which form a specification of the calls they are expected to receive. They can throw an exception if they receive a call they don't expect and are checked during verification to ensure they got all the calls they were expecting.

Any true service-oriented architecture should have these properties—but unfortunately many do not. However, the microservices movement has explicitly prioritized these architectural properties.

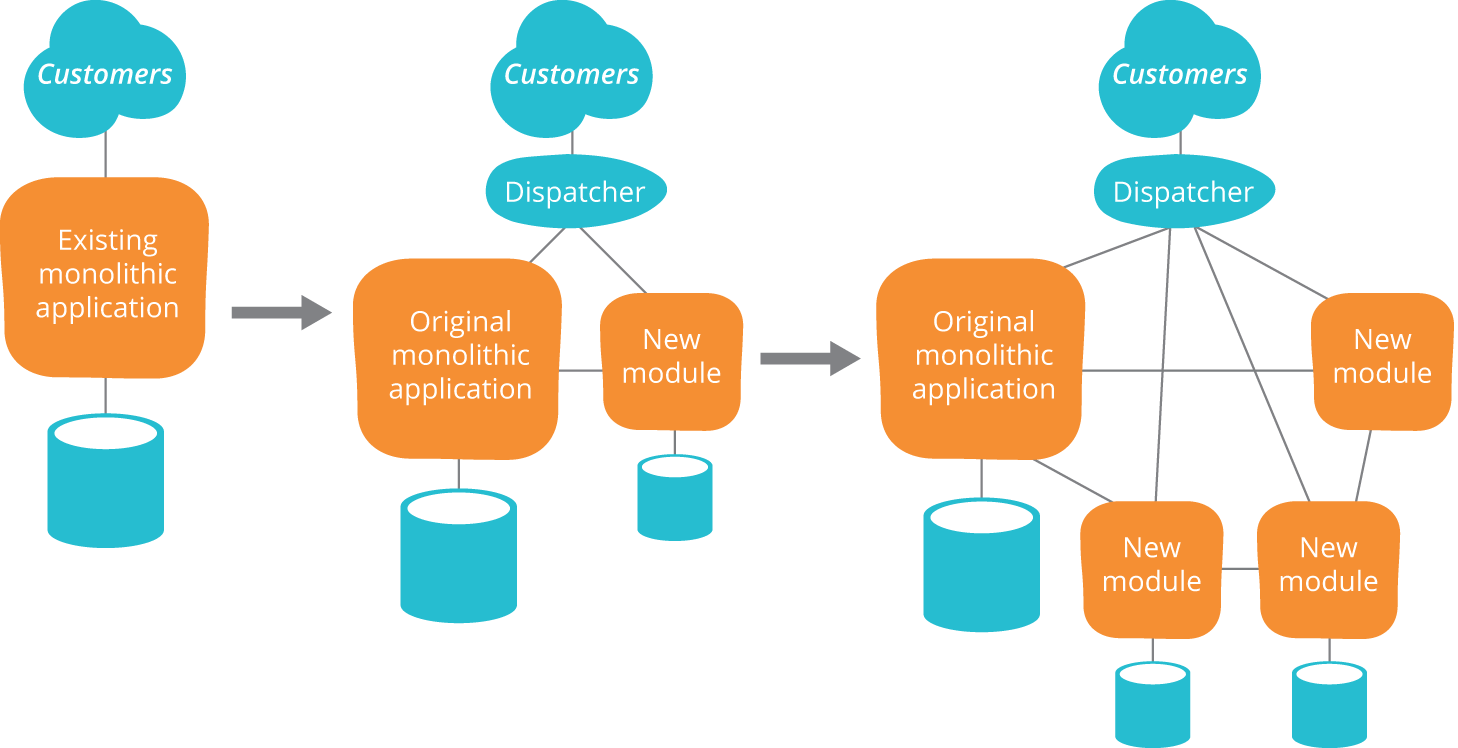

Of course, many organizations are living in a world where services are distinctly hard to test and deploy. Rather than re-architecting everything, we recommend an iterative approach to improving the design of enterprise system, sometimes known as evolutionary architecture. In the evolutionary architecture paradigm, we accept that successful products and services will require re-architecting during their lifecycle due to the changing requirements placed on them.

One pattern that is particularly valuable in this context is the strangler application. In this pattern, we iteratively replace a monolithic architecture with a more componentized one by ensuring that new work is done following the principles of a service-oriented architecture, while accepting that the new architecture may well delegate to the system it is replacing. Over time, more and more functionality will be performed in the new architecture, and the old system being replaced is "strangled".

Patterns

The Deployment Pipeline

The key pattern introduced in continuous delivery is the deployment pipeline. Our goal was to make deployment to any environment a fully automated, scripted process that could be performed on demand in minutes. We wanted to be able to configure testing and production environments purely from configuration files stored in version control. The apparatus we used to perform these tasks became known as deployment pipelines

In the deployment pipeline pattern, every change in version control triggers a process (usually in a CI server) which creates deployable packages and runs automated unit tests and other validations such as static code analysis. This first step is optimized so that it takes only a few minutes to run. If this initial commit stage fails, the problem must be fixed immediately; nobody should check in more work on a broken commit stage. Every passing commit stage triggers the next step in the pipeline, which might consist of a more comprehensive set of automated tests. Versions of the software that pass all the automated tests can then be deployed to production.

Deployment pipelines tie together configuration management, continuous integration and test and deployment automation in a holistic, powerful way that works to improve software quality, increase stability, and reduce the time and cost required to make incremental changes to software, whatever domain we're operating in. When building a deployment pipeline, the following practices become valuable:

- Only build packages once. We want to be sure the thing we're deploying is the same thing we've tested throughout the deployment pipeline, so if a deployment fails we can eliminate the packages as the source of the failure.

- Deploy the same way to every environment, including development. This way, we test the deployment process many, many times before it gets to production, and again, we can eliminate it as the source of any problems.

- Smoke test your deployments. Have a script that validates all your application's dependencies are available, at the location you have configured your application. Make sure your application is running and available as part of the deployment process.

- Keep your environments similar. Although they may differ in hardware configuration, they should have the same version of the operating system and middleware packages, and they should be configured in the same way. This has become much easier to achieve with modern virtualization and container technology.

With the advent of infrastructure as code, it has became possible to use deployment pipelines to create a fully automated process for taking all kinds of changes—including database and infrastructure changes

Patterns for Low-Risk Releases

In the context of web-based systems there are a number of patterns that can be applied to further reduce the risk of deployments. Michael Nygard also describes a number of important software design patterns which are instrumental in creating resilient large-scale systems in his book Release It!

The 3 key principles that enable low-risk releases are

- Optimize for Resilience. Once we accept that failures are inevitable, we should start to move away from the idea of investing all our effort in preventing problems, and think instead about how to restore service as rapidly as possible when something goes wrong. Furthermore, when an accident occurs, we should treat it as a learning opportunity. Resilience isn't just a feature of our systems, it's a characteristic of a team's culture. High performance organizations are constantly working to improve the resilience of their systems by trying to break them and implementing the lessons learned in the course of doing so.

- Low-risk Releases are Incremental. Our goal is to architect our systems such that we can release individual changes (including database changes) independently, rather than having to orchestrate big-bang releases due to tight coupling between multiple different systems.

- Focus on Reducing Batch Size. Counterintuitively, deploying to production more frequently actually reduces the risk of release when done properly, simply because the amount of change in each deployment is smaller. When each deployment consists of tens of lines of code or a few configuration settings, it becomes much easier to perform root cause analysis and restore service in the case of an incident. Furthermore, because we practice the deployment process so frequently, we’re forced to simplify and automate it which further reduces risk.